We think they had Cornelius Pearse in Dunderrow on 2 December 1835, and we know about Ellen Pearse born on 28 January 1843. There is an 8 year gap between the two so there were probably other children between these two.

And we know for sure that there was also Mary Pearse/Pierce, but I haven't found a baptismal record for her no matter what variation of spelling I use.

Family history and May Kiely told us that Mary Pierce married John (Jack) Keohane. I found a marriage listing for them in the Kinsale Church Registers for 28 January 1858. That would mean that Ellen Pierce was 15 years old at this time - so Mary was her older sister. Mary was likely born in 1840 or earlier.

There are many Keohanes in Kinsale at this time, but I could not find a baptismal record for John (Jack) Keohane. So we do not know how old he or Mary are - and we don't know where John is from or anything about his family.

But we do know that John Keohane and Mary Pierce somehow survive the famine. Let's take a quick detour to learn a little more about the Great Hunger in Cork, and how it might have affected our family.

I found an article in "The Journal of the Kinsale & District Local History Society" about the Kinsale area in the mid 1840s which was just before the Great Hunger and before Griffith's Valution of the 1850s. The British government had set up a commission to look at how the Irish land was occupied. They visited from town to town taking evidence from landowners and tenant farmers - although I guess no testimony from agricultural laborers. The commissioners visited Kinsale on 12 September 1844. "The minutes of the evidence taken are now held in the Boole Library of University College, Cork."

William R. Meade of Ballymartle House was working "as a Barrister in Dublin before he moved to the Ballymartle Estate in 1836." I am including the article's summary of his testimony because I think it gives us a feel for the conditions that our family experienced.

Here is a map of the civil parishes near Kinsale - Ballymartle is north of Kinsale and is close to Leighmoney and Dunderrow where many of our relatives were living.

William Meade "first was asked to describe the agriculture in the parish of Ballymartle:"

"The parish consists of two very different kinds of land. The part that is best managed consists of pretty good land, and is chiefly occupied by dairy farms. Part is very poor land and there is no dairy kept on it, it is principally occupied by small farmers. I think, except for draining and generally speaking, improving the agriculture, there is no very great improvement to the whole district practicable, it is all cultivated. The state of agriculture is improving very slowly, in my recollection. It has improved before I was acquainted with it, I understand. The principal manure used here is sea sand, besides the farm-yard manure or what they make as a substitute for it - the earth they collect from ditches and the sides of the fields. We have a farming society which we call the Kinsale Union Farming Society, it is making some improvements, but rather slowly. There was a farmers' farming society some years ago, which made great improvements, but in the distressed times, after the peace, it was broken up and from that time till lately there was no attempt at improving cultivation whatever. I think each farm is, on the average putting large and small together, about sixty acres, or something more, at present. I hold near 400 acres. The farms are all sizes but not many under twenty acres. On the good land the farms are generally large, on the poor land, they are generally small. The usual succession of crops grown are potatoes, wheat, oats, and sometimes that repeated again; and then they let the land rest until it will bear that rotation again. Of course, among the ordinary class of farmers, some are better than others. The general size of the grazing farms is 100 acres. Nothing under 100 acres can be called a Dairy Farm. I consider that they are increasing."

We saw that grazing was increasing when we were talking about the Moriartys in Kerry. Landlords wanted to get rid of the tenants who were subdividing the land they rented. The tenants would give a piece of land to their sons or sons-in-law to help support their family. Grazing cattle required less workers. And the land in Cork is so much better than in Kerry - it was well suited to grazing.

Next, Meade was asked about Landlord-Tenant Relations.

"There are some few farms held in common or joint-tenancy in the district. I believe they are diminishing as the leases expire. The rent in the district is fixed by proposal generally. The landlord certainly does not accept the highest offer - that would be very injudicious. The occupying tenants are scarcely ever discontinued in our district. There have been very few changes of tenure. There is some land let as high as 30 shillings - a small quantity. There is a good deal let at about one pound, and from that down to six or seven shillings the English acre ...

"The rule of most Landlords is to get one half-year of rent within the other. If one is due the 25th of March, they endeavor to get it before the 29th of September. Distraint is generally adopted to recover rent from defaulting tenants, but that is not generally the system - (Distraint is seizing a tenant's belongings in place of unpaid rent) ... it is generally to bring about a settlement. The distress is generally made at this time - September, the harvest, and I think the general agreement is, when there is a good deal of rent due, the landlord gets the grain crops, and the tenant the stock and potatoes and they are generally let to hold it till March subsequent - they give up the farm then."

"There are not a great many middlemen in the district and a great number of tenants hold at will. I do not think that the land on which there are old leases are a better bit cultivated. Generally the people are anxious for leases ( so they can not be evicted as easily.) I am sorry to say there is not a great deal of permanent improvements made in buildings. There is not a good farm-yard built; the tenant builds a house occasionally, and that is the chief sort of improvement. I think it is the habit for the landlord to contribute one half for permanent improvements - he provides timber and slates, in a great many instances. I do not know of any arrangements entered into between the landlord and the tenant, as to the improvement of the land. There has been no extensive system of the improvement of the land ...

"There is a very general anxiety among persons to divide the land among their sons; the proprietors in general, do not allow it and takes steps to prevent it according to the mode of tenure. If they hold at will they threaten to dispossess them entirely or else enforce the convention against the Subletting Act, where they hold by lease ... The large farmers in the area are better off than they were twenty years ago. There is more tendency to improve among the larger farmers than the smaller tenantry, the larger farms are better managed."

Then Mr. Meade was asked about the Laboring Class - this would be our relatives:

"I am afraid that labourers under the ordinary class of farmers are not improving. There is an anxiety among the gentry to have their laborers more comfortable, but it is not extended yet to the farmers. Their houses are very wretched indeed, in the northern part of the district. The laborers hold nothing under the farmers but their cabins. It is hard to say exactly what they usually pay for their cabins. The usual agreement between the farmer and the labourer is not a money matter; they get so much for their yearly labour; they get a house and so much potato ground, manure, barrels of coal, and some other things. They do not get any money and they make fresh agreement every year. Scarcely any of the better class of farmers give any money to their labourers. I do not think the system at all a desirable one. The quantity of ground that they have from the farmers depends largely on the quality of the ground. They would rather have one acre of good potato ground than two bad ones. They are very anxious to get good potato ground. It varies from one acre to two. When men are hired by the day by the farmers, which is not often done, they are paid 8 pence a day or 5 pence and their diet. No man will take a labourer on the 25th of March unless he ascertains that he has potatoes enough to sustain him till his potatoes come in; and then he has only to depend upon casual employment, which is rare and they are then reduced to very great distress. There have been no agrarian outrages in my recollection. This has always been, I believe, a particularly quiet district."

Next, the question for Mr. Meade was about estate management:

"There is a great difference in the management of estates under absentee proprietors, of course. Generally speaking, the estates of absentee proprietors are much worse managed in some parts of the south of Ireland. Larger estates are better managed than small ones."

(William Richard Meade died in 1894 and was succeeded by his nephew, Major Richard John Meade, who lived there until 1955.)

Ruins of Ballymartle House.

The dead were buried without coffins just a few inches below the soil, to be gnawed at by rats and dogs. In some cabins, the dead remained for days or weeks among the living who were too weak to move the bodies outside. In other places, unmarked hillside graves came into use as big trenches were dug and bodies dumped in, then covered with quicklime.

The dead were buried without coffins just a few inches below the soil, to be gnawed at by rats and dogs. In some cabins, the dead remained for days or weeks among the living who were too weak to move the bodies outside. In other places, unmarked hillside graves came into use as big trenches were dug and bodies dumped in, then covered with quicklime.

Soon after the commission questioned Mr. Meade, famine hits Cork.

The website http://www.failteromhat.com/southernstar/page10.php has this description:

"When Famine Devastated West Cork

The Famine sparked off a decline in the Irish population which lasted half a century ... One of the major disasters of the nineteenth century, the Famine marked a great divide in modern Irish History and, through the impact of emigration, its effects spread far beyond Irish shores. Cork and especially West Cork were among the worst hit areas.

It is hard to believe that the invasion of the tiny potato killing fungus 'Phythophthora infestans" could result in the Great Famine of 1846/47 and the death of a million people out of a population of eight and a half. But it was not solely the loss of the potato crop which ended in death; combined with a rigid doctrinaire attitude to famine relief and widespread absentee landlords, it was a deadly mix.

It is hard to believe that the invasion of the tiny potato killing fungus 'Phythophthora infestans" could result in the Great Famine of 1846/47 and the death of a million people out of a population of eight and a half. But it was not solely the loss of the potato crop which ended in death; combined with a rigid doctrinaire attitude to famine relief and widespread absentee landlords, it was a deadly mix.

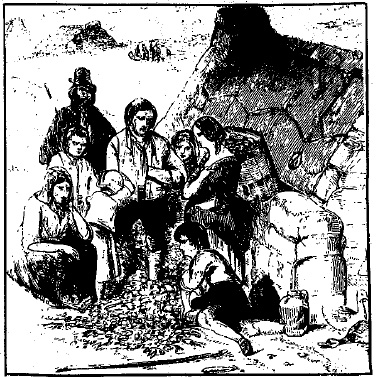

Soup Kitchens

Food for the Government relief schemes was stored in depots but was only available at a high price and most tenant farmers were too poor to afford it. Instead, they went to soup kitchens, many overflowing, unable to cope with the numbers which arrived at their doors. They died outside the doors.

Burying the dead became more and more of a problem resulting in the rapid spread of disease. There were reports of hinged coffins and mass open graves. Today, there are ruined workhouses all over the country and famine memorials alone survive to remind us of those dreadful times, not even a hundred and fifty years ago.

To paint an accurate picture of the society on which famine visited, we must look at the report of the Devon Commission of February, 1845. This was a Royal Commission chaired by the Earl of Devon which visited every point of Ireland as a response to Daniel O'Connell's monster meetings which had been taking place all over the country.

Burying the dead became more and more of a problem resulting in the rapid spread of disease. There were reports of hinged coffins and mass open graves. Today, there are ruined workhouses all over the country and famine memorials alone survive to remind us of those dreadful times, not even a hundred and fifty years ago.

To paint an accurate picture of the society on which famine visited, we must look at the report of the Devon Commission of February, 1845. This was a Royal Commission chaired by the Earl of Devon which visited every point of Ireland as a response to Daniel O'Connell's monster meetings which had been taking place all over the country.

Destitute

It describes how a peasantry had been created which was one of the most destitute in Europe. "It would be impossible to adequately to describe," stated the Devon Commission in its Report, "the privations which they (the Irish labourer and his family) habitually and silently endure ... in many districts their only food is the potato, their only beverage water ... their cabins are seldom a protection against the weather ... a bed or a blanket is a rare luxury ... and nearly in all their pig and a manure heap constitute their only property." The Commissioners could not "forbear expressing our strong sense of the patient endurance which the labouring classes have exhibited under sufferings greater, we believe, than the people of any other country in Europe have to sustain."

Add to this the fact that before the famine, between 1779 and 1841, the population increased dramatically by 172%, and you have a recipe for disaster.

A great part of the poverty was created by many absentee landlords who extracted large rents out of their tenants. The Devon Commission reported that the main cause of Irish misery was bad relations between landlord and tenant, the result of years of rebellion and punitive legislation. Eventually, the country became simply a source of rents which were spent elsewhere. In 1842 it was estimated that 6 million pounds was going out of Ireland. The German traveler Kohl commented on the mansions of absentee landlords standing "stately, silent and empty". Absolute power was left in the hands of an agent whose worth was measured by the amount of money he could extract.

During the eighteenth century, a system of middlemen developed when large tracts of land were let to one person who then sub-let small amounts. Any improvement resulted in a rent increase and so the tenant was deprived of any incentive or security. In addition there was very little regular agricultural work for labourers or "spailpins" because the farms were too small to employ them, except at potato picking time. Unless a labourer could get a patch of land to grow potatoes, he and his family would starve for thirty weeks of the year. And so the scene was set for the famine. Then potatoes turned black overnight and were inedible.

Even so, grain was being exported from the country throughout the period. Charles Edward Treverlyan, the Head of the Treasury, refused to restrict trade and ban its export. Only large ports such as Cork and Belfast knew anything about import, ports in the West being solely geared to export. And so a country starved while its food fed other mouths than its own.

Add to this the fact that before the famine, between 1779 and 1841, the population increased dramatically by 172%, and you have a recipe for disaster.

A great part of the poverty was created by many absentee landlords who extracted large rents out of their tenants. The Devon Commission reported that the main cause of Irish misery was bad relations between landlord and tenant, the result of years of rebellion and punitive legislation. Eventually, the country became simply a source of rents which were spent elsewhere. In 1842 it was estimated that 6 million pounds was going out of Ireland. The German traveler Kohl commented on the mansions of absentee landlords standing "stately, silent and empty". Absolute power was left in the hands of an agent whose worth was measured by the amount of money he could extract.

During the eighteenth century, a system of middlemen developed when large tracts of land were let to one person who then sub-let small amounts. Any improvement resulted in a rent increase and so the tenant was deprived of any incentive or security. In addition there was very little regular agricultural work for labourers or "spailpins" because the farms were too small to employ them, except at potato picking time. Unless a labourer could get a patch of land to grow potatoes, he and his family would starve for thirty weeks of the year. And so the scene was set for the famine. Then potatoes turned black overnight and were inedible.

Even so, grain was being exported from the country throughout the period. Charles Edward Treverlyan, the Head of the Treasury, refused to restrict trade and ban its export. Only large ports such as Cork and Belfast knew anything about import, ports in the West being solely geared to export. And so a country starved while its food fed other mouths than its own.

Great Hunger

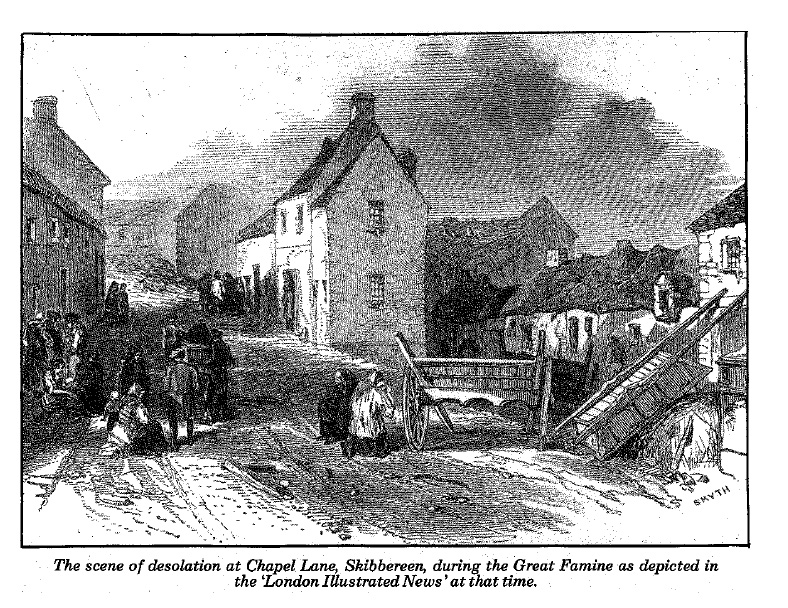

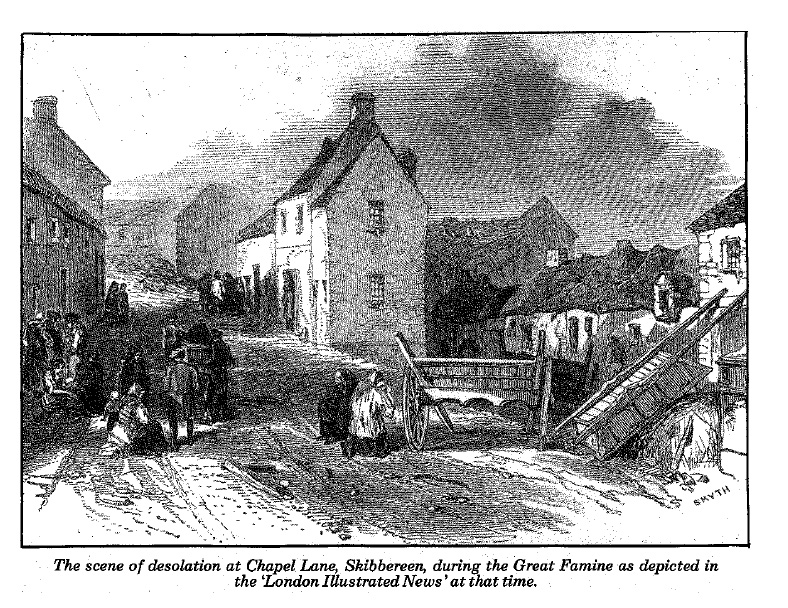

People lived exclusively on potatoes in many areas including West Cork, Kerry, Donegal and the west of the Shannon. In those areas Government food depots were setup as fear of famine became a possibility. In Skibbereen, it was in the charge of Commissariat Officer, Mr. Hughes, who was answerable to Sir Randolph Routh, Commissary General. Cecil Woodham-Smith tells the story in "The Great Hunger", of how starvation was first reported from Skibbereen: "One market day; September 12, 1846, in Skibbereen, County Cork, an agricultural centre, there was not a single loaf of bread or pound of meal to be had in the town." The Relief Committee applied to Mr. Hughes, the Commissariat Officer, asking him to sell or lend some meal from the Government depot. He refused, saying "his instructions prevented him" and an angry scene followed. Two days later, members of the Committee again came to see him, followed by a starving crowd, imploring for food. The sight was too much for Mr. Hughes. The misery in Skibbereen, he assured Routh on September 20, had not been exaggerated, and he issued two and a half tons of meal, instantly distributed in small lots. Upon this, the Catholic curate of Trellagh, a neighbouring village, came asked for two tons, telling Mr. Hughes his people were starving and he dared not return empty-handed. Again Mr. Hughes gave way. The curate of Trellagh was followed by the Relief Committee of the village of Leap, who asked for ten tons. Mr. Hughes refused, and a most painful scene took place. In the presence of Captain Dyer, the Board of Works' inspecting officer, and Mr. Pinchen, sub-inspector of Police, the spokesman for the Relief Committee of Leap said : "Mr. Deputy Commissary, do you refuse to give out food to starving people who are ready to pay for it? If so, in the event of an outbreak tonight the responsibility will be yours." What, Mr. Hughes asked Routh, was the right course for him to pursue? Routh, in reply instructed Mr. Hughes to "represent to applicants for Government supplies of food the necessity for private enterprise and importation ... Towns should combine and import from Cork or Liverpool .. Now is the time to use home produce."

By September 25 the people at Clashmore, County Waterford were living on blackberries, and at Rathcormack County Cork, on cabbage leaves.

Serious riots took place in Youghal where the sight of food being exported was unbearable to the starving people. On 25th September, 1846 an enraged crowd tried to hold up a boat about to sail laden with oats. Police sent for troops, who, with difficulty, stopped the crowd at Youghal Bridge. It was serious enough for the Under Secretary at Dublin Castle, Mr. T.N. Redington, to be sent over to London to explain to the British Government what had happened.

As autumn turned to the winter of 1846, the wild foods on which people had existed such as nettles, blackberries and cabbage leaves began to wither and children began to die. Fifty per cent of children admitted to the workhouses after October, 1846 died of "diarrhoea acting on an exhausted constitution."

By November famine had reached such a point that disorganisation began to set in. Starving mobs of men roamed the countryside like wolves hunting for food. The employment lists for public works which should have been prepared by the local relief committees became a farce as committee men were threatened with losing their lives. Delays in paying wages increased the trouble.

By September 25 the people at Clashmore, County Waterford were living on blackberries, and at Rathcormack County Cork, on cabbage leaves.

Serious riots took place in Youghal where the sight of food being exported was unbearable to the starving people. On 25th September, 1846 an enraged crowd tried to hold up a boat about to sail laden with oats. Police sent for troops, who, with difficulty, stopped the crowd at Youghal Bridge. It was serious enough for the Under Secretary at Dublin Castle, Mr. T.N. Redington, to be sent over to London to explain to the British Government what had happened.

As autumn turned to the winter of 1846, the wild foods on which people had existed such as nettles, blackberries and cabbage leaves began to wither and children began to die. Fifty per cent of children admitted to the workhouses after October, 1846 died of "diarrhoea acting on an exhausted constitution."

By November famine had reached such a point that disorganisation began to set in. Starving mobs of men roamed the countryside like wolves hunting for food. The employment lists for public works which should have been prepared by the local relief committees became a farce as committee men were threatened with losing their lives. Delays in paying wages increased the trouble.

In Clonakilty (Not so far from Kinsale)

When a man names Denis McKennedy died on October 24 while working on Road No. 1, in the western division of West Carbery, at Caheragh, it was alleged he had not been paid since October 10. A post mortem examination was carried out by Dr. Daniel Donovan and Dr. Patrick Due, and death was pronounced to be the results of starvation. There was no food in the stomach or in the small intestines, but in the large intestine was a "portion of undigested raw cabbage, mixed with excrement." At the coroner's inquest a verdict was returned that the deceased "died of starvation caused by the gross neglect of the Board of Works." At Bandon, where three weeks' wages were owing on October 31, deaths were alleged to have occurred.

Charles Trevelyan, the Head of the Treasury, still maintained that enough had been done to help Ireland and so the situation gradually became even worse. In Skibbereen starvation had been reported at the beginning of September and exactly three months later, two Protestant clergymen, Mr. Caulfield and Mr. Townshend went to see him in London.

They said that the Government plans for relief were not working in their town because the call for "practical and influential persons of property and respectability" to help organise the relief had not been answered. No subscription had been raised and the committee was in a state of suspension and useless. They told him only eight pence a day was paid for working on the public road and was not enough to feed a family. About seventy people were given soup every day at Mr. Caulfield's house and would otherwise starve. The two clergymen implored the Government to send food but nothing was done.

Days later, on 15th December, Trevelyan even wrote to Commissary General Routh referring to "what is now going on in Skibbereen" and telling him not to send Government supplies because a relief committee was not operating in the area. "Principles must be kept in view," he wrote. Nobody questioned what principals."

Charles Trevelyan, the Head of the Treasury, still maintained that enough had been done to help Ireland and so the situation gradually became even worse. In Skibbereen starvation had been reported at the beginning of September and exactly three months later, two Protestant clergymen, Mr. Caulfield and Mr. Townshend went to see him in London.

They said that the Government plans for relief were not working in their town because the call for "practical and influential persons of property and respectability" to help organise the relief had not been answered. No subscription had been raised and the committee was in a state of suspension and useless. They told him only eight pence a day was paid for working on the public road and was not enough to feed a family. About seventy people were given soup every day at Mr. Caulfield's house and would otherwise starve. The two clergymen implored the Government to send food but nothing was done.

Days later, on 15th December, Trevelyan even wrote to Commissary General Routh referring to "what is now going on in Skibbereen" and telling him not to send Government supplies because a relief committee was not operating in the area. "Principles must be kept in view," he wrote. Nobody questioned what principals."

Here is another report from http://www.historyplace.com/worldhistory/famine/hunger.htm.

"Many of the rural Irish had little knowledge of money, preferring to live by the old barter system, trading goods and labor for whatever they needed. Any relief plan requiring them to purchase food was bound to fail. In areas where people actually had a little money, they couldn't find a single loaf of bread or ounce of corn meal for sale. Food supplies in 1846 were very tight throughout all of Europe, severely reducing imports into England and Ireland. European countries such as France and Belgium outbid Britain for food from the Mediterranean and even for Indian corn from America.

Meanwhile, the Irish watched with increasing anger as boatloads of home-grown oats and grain departed on schedule from their shores for shipment to England. Food riots erupted in ports such as Youghal near Cork where peasants tried unsuccessfully to confiscate a boatload of oats. At Dungarvan in County Waterford, British troops were pelted with stones and fired 26 shots into the crowd, killing two peasants and wounding several others. British naval escorts were then provided for the riverboats as they passed before the starving eyes of peasants watching on shore.

As the Famine worsened, the British continually sent in more troops. "Would to God the Government would send us food instead of soldiers," a starving inhabitant of County Mayo lamented.

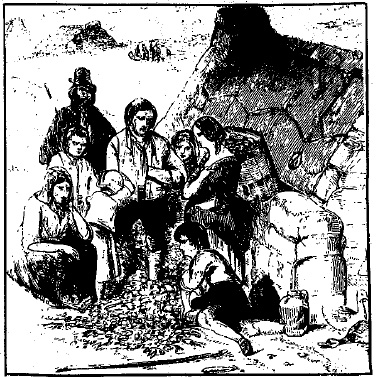

The Irish in the countryside began to live off wild blackberries, ate nettles, turnips, old cabbage leaves, edible seaweed, shellfish, roots, roadside weeds and even green grass. They sold their livestock and pawned everything they owned including their clothing to pay the rent to avoid certain eviction and then bought what little food they could find with any leftover money. As food prices steadily rose, parents were forced to listen to the endless crying of malnourished children.

Fish, although plentiful along the West Coast of Ireland, remained out of reach in water too deep and dangerous for the little cowhide-covered Irish fishing boats, known as currachs. Starving fishermen also pawned their nets and tackle to buy food for their families.

Making matters worse, the winter of 1846-47 became the worst in living memory as one blizzard after another buried homes in snow up to their roofs. The Irish climate is normally mild and entire winters often pass without snow. But this year, an abrupt change in the prevailing winds from southwest into the northeast brought bitter cold gales of snow, sleet and hail.

Black Forty-Seven

Amid the bleak winter, hundreds of thousands of desperate Irish sought work on public works relief projects. By late December 1846, 500,000 men, women and children were at work building stone roads. Paid by piece-work, the men broke apart large stones with hammers then placed the fragments in baskets carried by the women to the road site where they were dumped and fit into place. They built roads that went from nowhere to nowhere in remote rural areas that had no need of such roads in the first place. Many of the workers, poorly clothed, malnourished and weakened by fever, fainted or even dropped dead on the spot.

The men were unable to earn enough money to adequately feed themselves let alone their families as food prices continued to climb. Corn meal now sold for three pennies a pound, three times what it had been a year earlier. As a result, children sometimes went unfed so that parents could stay healthy enough to keep working for the desperately needed cash.

A first-hand investigation of the overall situation was conducted by William Forster, a member of the Quaker community in England. He was acting on behalf of the recently formed Central Relief Committee of the Society of Friends, with branches in Dublin and London. The children, Forster observed, had become "like skeletons, their features sharpened with hunger and their limbs wasted, so that little was left but bones, their hands and arms, in particular, being much emaciated, and the happy expression of infancy gone from their faces, leaving behind the anxious look of premature old age."

Nicholas Cummins, the magistrate of Cork, visited the hard-hit coastal district of Skibbereen. "I entered some of the hovels," he wrote, "and the scenes which presented themselves were such as no tongue or pen can convey the slightest idea of. In the first, six famished and ghastly skeletons, to all appearances dead, were huddled in a corner on some filthy straw, their sole covering what seemed a ragged horsecloth, their wretched legs hanging about, naked above the knees. I approached with horror, and found by a low moaning they were alive -- they were in fever, four children, a woman and what had once been a man. It is impossible to go through the detail. Suffice it to say, that in a few minutes I was surrounded by at least 200 such phantoms, such frightful spectres as no words can describe, [suffering] either from famine or from fever. Their demoniac yells are still ringing in my ears, and their horrible images are fixed upon my brain."

The dead were buried without coffins just a few inches below the soil, to be gnawed at by rats and dogs. In some cabins, the dead remained for days or weeks among the living who were too weak to move the bodies outside. In other places, unmarked hillside graves came into use as big trenches were dug and bodies dumped in, then covered with quicklime.

The dead were buried without coffins just a few inches below the soil, to be gnawed at by rats and dogs. In some cabins, the dead remained for days or weeks among the living who were too weak to move the bodies outside. In other places, unmarked hillside graves came into use as big trenches were dug and bodies dumped in, then covered with quicklime.

Most died not from hunger but from associated diseases such as typhus, dysentery, relapsing fever, and famine dropsy, in an era when doctors were unable to provide any cure. Highly contagious 'Black Fever,' as typhus was nicknamed since it blackened the skin, is spread by body lice and was carried from town to town by beggars and homeless paupers. Numerous doctors, priests, nuns, and kind-hearted persons who attended to the sick in their lice-infested dwellings also succumbed. Rural Irish, known for their hospitality and kindness to strangers, never refused to let a beggar or homeless family spend the night and often unknowingly contracted typhus. At times, entire homeless families, ravaged by fever, simply laid down along the roadside and died, succumbing to 'Road Fever.'

Soup Kitchens

Trevelyan's public works relief plan for Ireland had failed. At its peak, in February and March of 1847, some 700,000 Irish toiled about in useless projects while never earning enough money to halt starvation.

Now, in Cork harbor, the long-awaited private enterprise shipments of Indian corn and other food supplies had finally begun arriving. Food prices dropped by half and later dropped to a third of what they had been, but the penniless Irish still could not afford to eat. As a result, food accumulated in warehouses within sight of people walking about the streets starving.

Between March and June of 1847, the British government gradually shut down all of the public works projects throughout Ireland. The government, under the direction of Prime Minister Russell, had decided on an abrupt change of policy "to keep the people alive." The starving Irish were now to be fed for free through soup kitchens sponsored by local relief committees and by groups such as the Quakers and the British Relief Association, a private charity funded by prosperous English merchants.

The Soup Kitchen Act of 1847 called for the food to be provided through taxes collected by local relief committees from Irish landowners and merchants. But little money was ever forthcoming. Ireland was slowly going bankrupt. Landlords, many of whom were already heavily in debt with big mortgages and unpaid loans, were not receiving rents from their cash-strapped tenants. Merchants also went broke, closed up their shops, then joined the ranks of the dispossessed, begging on the streets.

Daily soup demand quickly exceeded the limited supply available. In Killarney, there was just one soup kitchen for 10,000 persons. Cheap soup recipes were improvised containing stomach-turning combinations of old meat, vegetables, and Indian corn all boiled together in water. To a people already suffering from dysentery, the watery stew could be a serious health risk. Many refused to eat the "vile" soup after just one serving, complaining of severe bowel problems. Another dislike was the requirement for every man, woman and child to stand in line while holding a small pot or bowl to receive their daily serving, an affront to their pride.

By the spring, Government-sponsored soup kitchens were established throughout the countryside and began dispensing 'stirabout,' a more substantial porridge made from two-thirds Indian corn meal and one-third rice, cooked with water. By the summer, three million Irish were being kept alive on a pound of stirabout and a four-ounce slice of bread each day. But the meager rations were not enough to prevent malnutrition. Many adults slowly starved on this diet.

In the fall of 1847, the third potato harvest during the Famine brought in a blight-free crop but not enough potatoes had been planted back in the spring to sustain the people. The yield was only a quarter of the normal amount. Seed potatoes, many having been eaten, had been in short supply. Planters had either been involved in the public works projects or had been too ill to dig. Others were simply discouraged, knowing that whatever they grew would be seized by landowners, agents or middlemen as back payment for rent. The rough winter had also continued to wreak havoc into March and April with sleet, snow, and heavy winds, further delaying planting. Seed for alternative crops such as cabbage, peas and beans, had been too expensive for small farmers and laborers to buy.

Many landlords, desperate for cash income, now wanted to grow wheat or graze cattle and sheep on their estates. But they were prevented from doing so by the scores of tiny potato plots and dilapidated huts belonging to penniless tenants who had not paid rent for months, if not years. To save their estates from ruin, the paupers would simply have to go.

Copyright © 2000 The History Place™ All Rights Reserved"

The famine and its effects did not end for years. The following is an email I received from the Kerry Roots mailing list.

'Extacts from the Diary of Richard Cannon Smiddy, County Cork

1849

There was a fearful visit from the cholera to this country and in fact to

all Europe and America during the past summer. Many died of it in this town

where it raged with particular virulence during the space of a fortnight,

and it lingered less fatal, for a considerable time afterwards.

It is, I find, a long time since I noted any matter in these pages, not

even the departure of the old year or the opening of the new. The people and

the country are still struck down under the effects of the famine arising

from four successive failures of the potato.

There seems to be no hope of reviving life, and even the upper classes,

especially those depending on landed property, appear to be moving too, to

the verge of ruin. Out of this suffering good might yet arise to the great

bulk of the population of this country, and if so, it will be by passing,

surely, through a fearful ordeal.

These are the effects of misrule and oppression - agents, which have been

for centuries at work in poor Ireland. May she arise, and may the morning of

her resurrection be as glorious as the night, for her doom has been long and

dismal.

June 1851

This appears to be a fine and most promising season. The potatoes as yet

exhibit no sign of disease, and it is hoped that, with Gods blessing, we

shall have a good crop of them.

England is at present exhibiting its bigotry and infatuation in the passing

of a penal law against the Catholics by way of repelling what they term "

Papal Aggression".

That proud land may have cause to regret this yet, and that she may!

August 1851.

The Potato Disease. This mysterious disease has made its appearance in the

country since the beginning of the month. The new species of potato are

escaping best, though they too are touched, while among the old seeds the

disease has even already committed very extensive injury. In many districts

of the country, a large portion of the harvest is already cut down. It is

stated that the various grains, particularly wheat, have not been so good

for many years.

November 1851.

I have indeed but very little to add here since the last entry. The potato

disease has gone on, even increasing, to such an extent, that the root, as

it is stated, is in many districts worse than it has been for the last four

or five years.

Even at this inclement season of the year, is going on rapidly that

emigration stream to America, which has already drained this country of so

many hundreds of thousands of its stalwart population.

Many predict that in a few years this fine old country will be almost a

wilderness, the lonely habitation of a few men and of multitudes of cattle.'

Regards Sandra"

Griffith's Valuation of Cork shows many Keohanes in the 1850s between Bantry and Skibbereen which is a distance from Kinsale. This was taken not that long after the fame There were no Keohanes listed in Kinsale. So does that mean that the Keohanes in the Kinsale Church Registers at that time were not renting any land? Were they all agricultural laborers?

Let's go back to the Kinsale Parish marriage register for 28 January 1858 which lists J. Keliher marrying John Keohane and Mary Pierce (spelling has changed.) Witnesses are Charles Pierce and Ellen Keohane. The last column states "John Keohane to Mary Pierce."

I know that John and Mary Keohane have a son Patrick Keohane who is my grandfather's father.

So I went through www.irishgenealogy.ie, and I found several children with parents of these same names. Let's take a look at them next.

Hi Mary. Glad you find my article on William R Meade's testimony to the Devon Commission useful. I have a portrait of William R Meade and some photos of Ballymartle House before it went to ruin if you are interested. All the best. Fergal Browne

ReplyDeleteHi Fergal,

DeleteI apologize - I just saw your comment. I never think that anyone reads this blog so never look for comments!!

I would love to see what William Meade looked like and the house as well.

My husband is from Sneem and we lived there for a few years so I know a lot about the Sneem area where my Moriarty relatives are from, but I know almost nothing about the Kinsale area. I have visited there several times, but most of what I know is from research. And it is fascinating reading.

Thanks so much for getting in touch - and I apologize for the delay in getting back to you.